A PRAYER FOR MY BROTHERS

by CHANTINE AKIYAMA POH

I have been thinking about my younger brother Chyle a lot lately, since he graduated from college this past May. My parents and I were really excited when he got into college, and then again when he made the grades to graduate–but now he has to find a job, and we’re holding our breath.

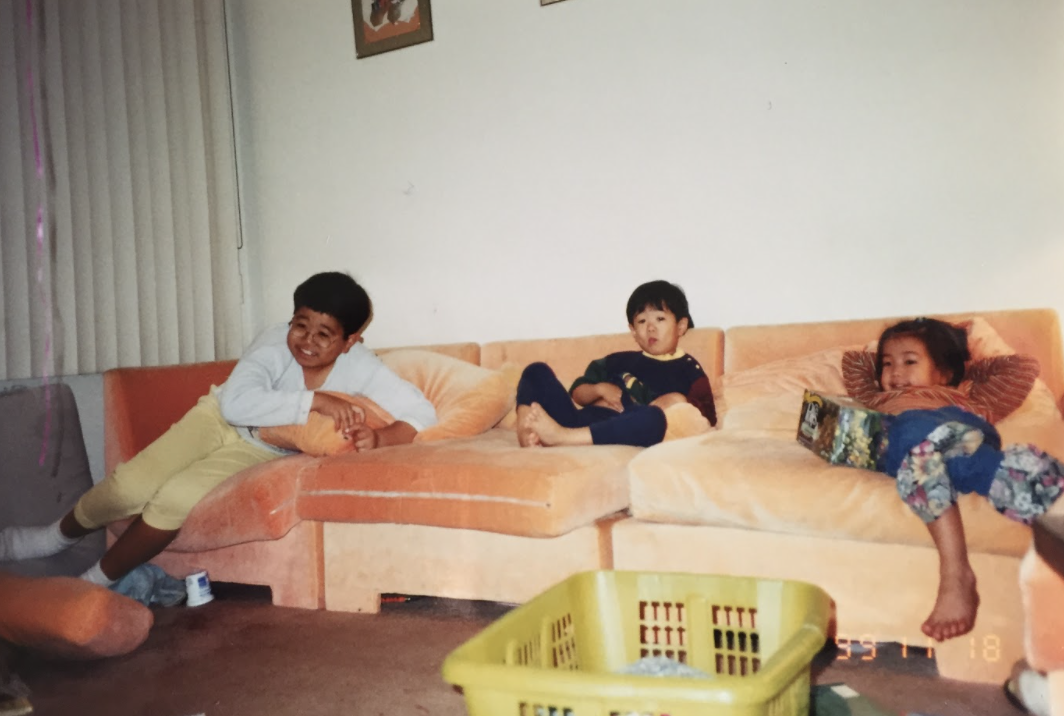

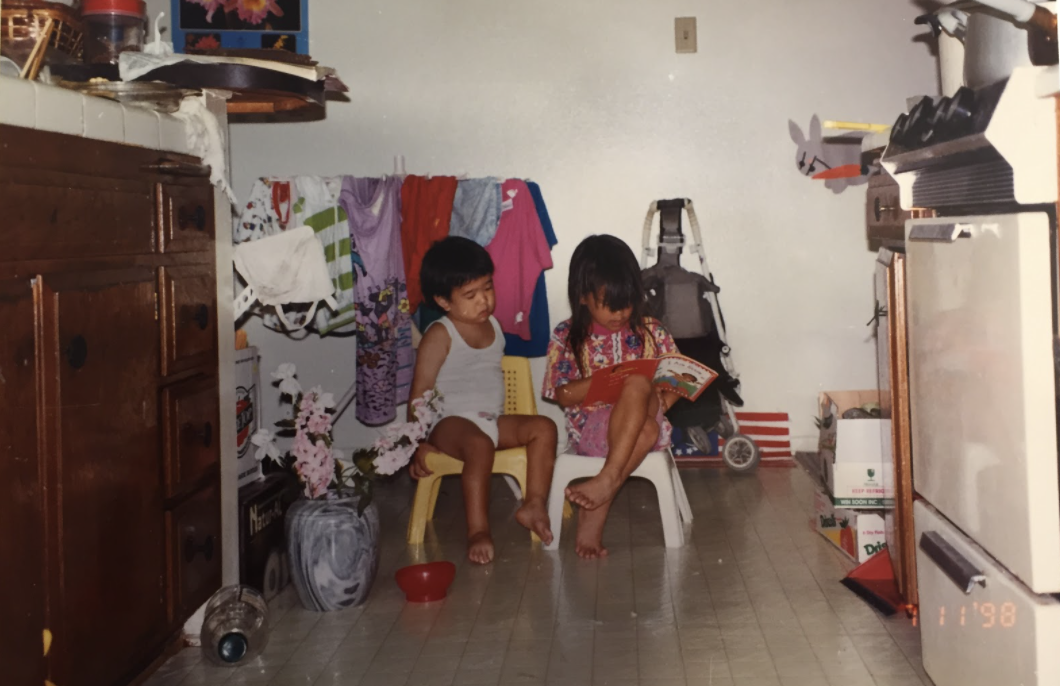

Chyle is the sweetest kid I know. He’s 24 but I still remember his teardrop-shaped baby eyes. He looked like one of those Precious Moments dolls sold in Hallmark stores in the 90s. He’s gentle, quiet, loves to socialize, loves the large TV my parents gave him for graduation, and he really loves food. Because he’s remarkably patient, I have always said Chyle was the most like Jesus out of anyone in our family.

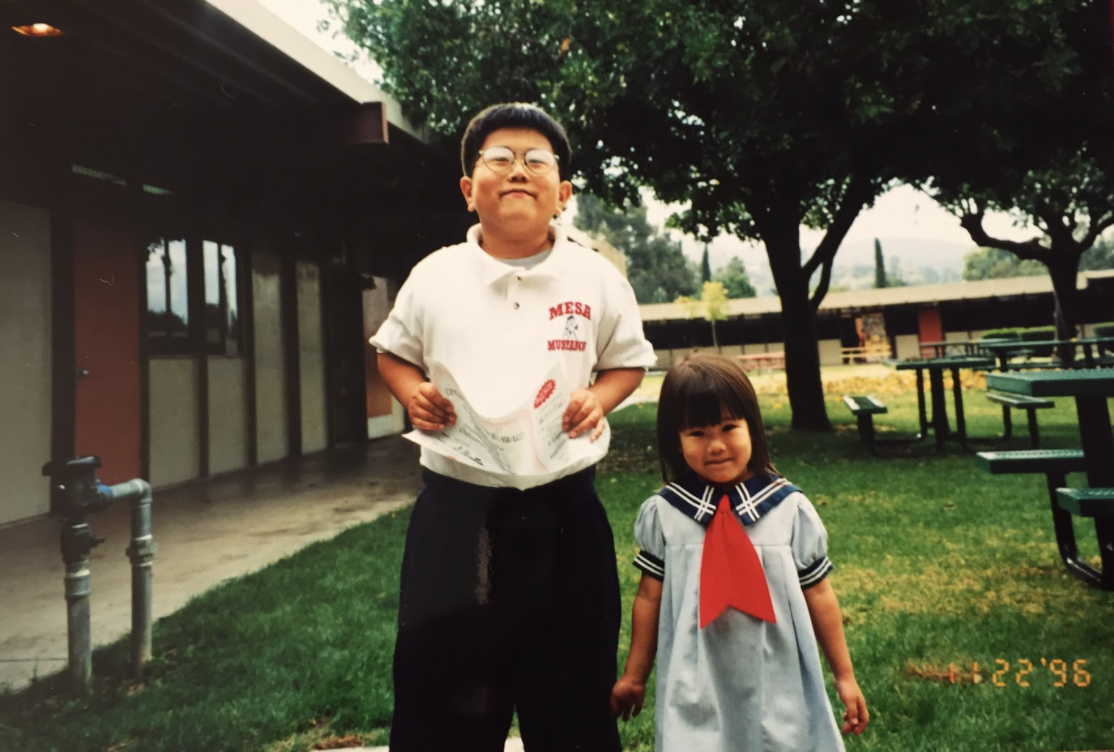

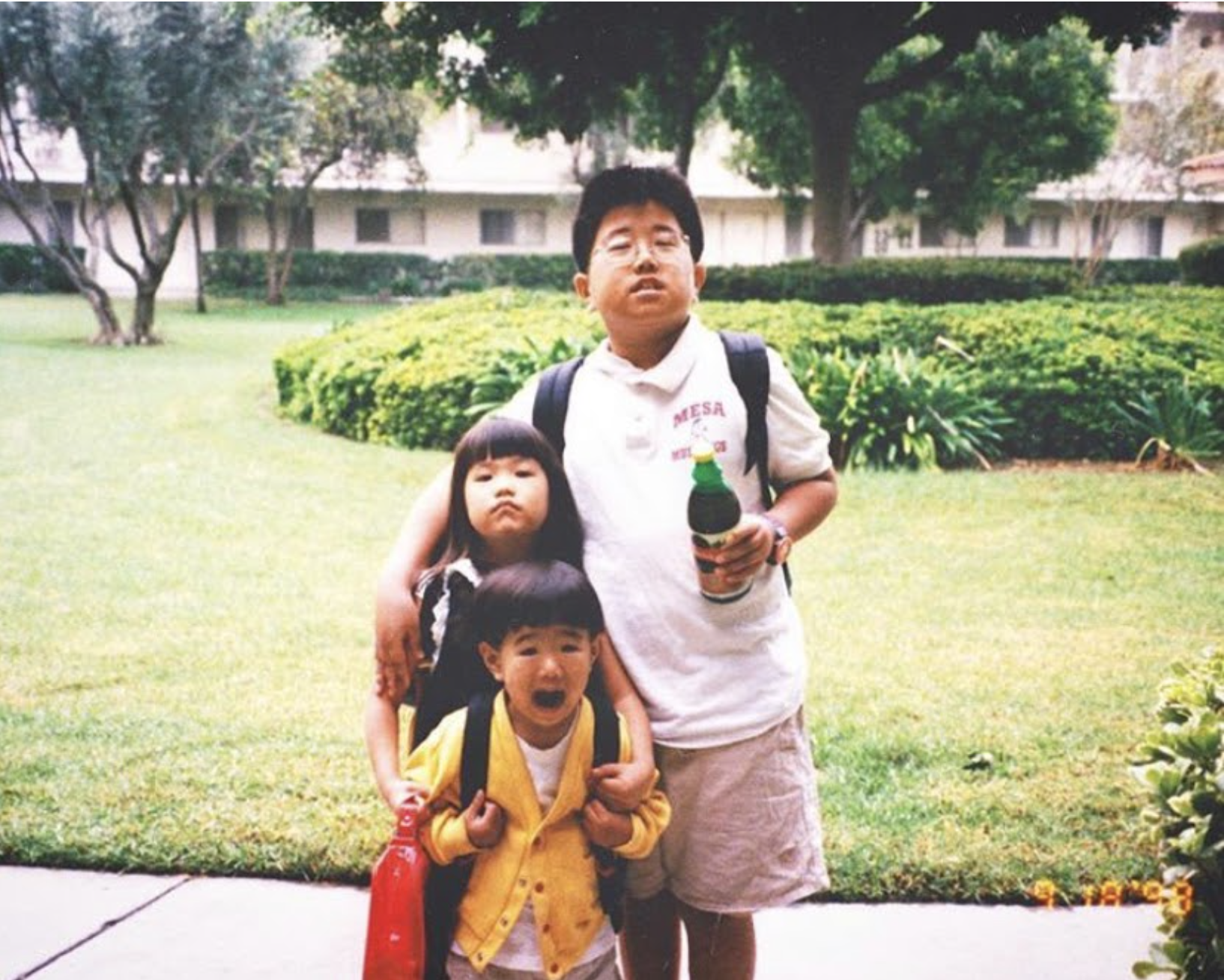

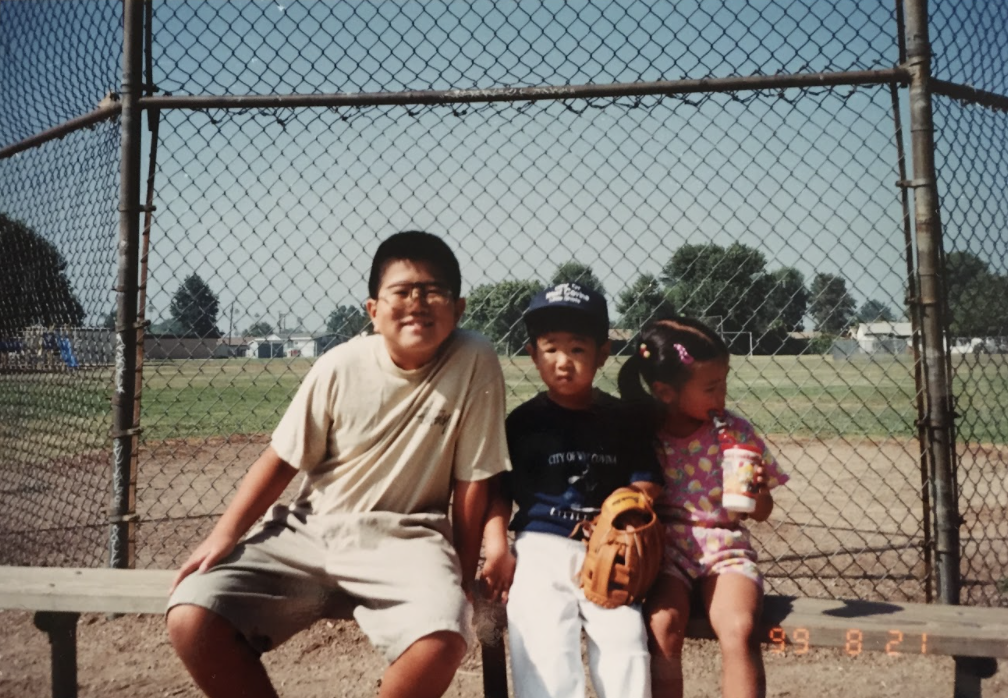

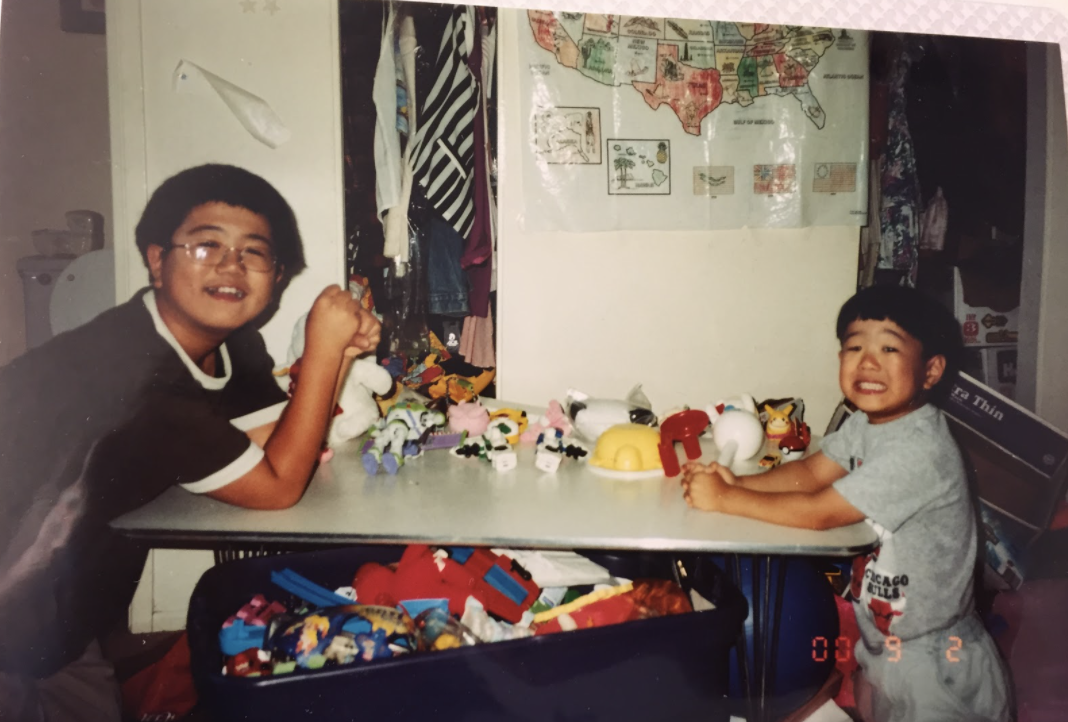

As the only girl in the family, I was definitely the most spoiled sibling, but Chyle never complained, was never jealous, and, most amazingly, has forgiven me for all of the bullying I put him through when we were children. Believe me: it would take a saint to forgive me for some of the things that I did to him! Chyle also has autism, which makes it hard for him to talk to people face-to-face. But this has made him an expert texter and GIF-finder: a digital king among his Gen-Z peers.

My older brother, Conrad, also has autism. He is talkative and strong-willed (like me), loves basketball, loves his massive Jordan and basketball collections, and really loves me. He’s my big bro! He pushed me around in the stroller when I was a baby! And he still calls me every Thursday evening, without fail. Because of his diagnosis, my parents went on a soul-searching journey that led them through all sorts of temples and religions, finally to Jesus. When Conrad was in school, special education was not what it is today, and I believe he wasn’t given the opportunities to express his full potential. I yearn for more for Conrad—for him to have the fullest possible life on this earth. This prayer has been a perpetual ache in my heart for as long as I can remember.

But what does a full life look like for someone with disabilities? Many American protestant churches often talk about “loving the least of these,” but I haven’t heard many people theologizing or celebrating the spirituality of those with disabilities, except with the mindset of “fixing” them through prayer. In some charismatic denominations, disabilities are treated like occasions for troubleshooting. God doesn’t want people to be imperfect, so be HEALED in Jesus’ name! See you next week.

Most of these ministers wouldn’t know how to live with my brothers. They wouldn’t know how to care for their social wounds, inflicted by the mean stares and patronizing smiles of church congregants. They haven’t had to patiently wait for them to formulate thoughts that may never find verbal expression, to yearn for society to slow down just enough to recognize the talents and Christlikeness within them right now, as they are.

Of course I want them to be fully able-bodied and healthy in this life. But how can we yearn for others to be healthy if we cannot have the healthy curiosity to slow down and ask them: Who are you? What are your dreams? What do you think your destiny is? Tish Warren, in The Liturgy of the Ordinary, wonders about this on behalf of a friend’s mentally disabled daughter whose brain, as far as they knew, can’t sustain thought. She asks: “What would it mean for this young girl to grow in faith?... In what way might she worship? I began to hunger for a faith that was not merely cognitive, not simply about achieving the right intellectual beliefs.” For Warren, this hunger led her to the Anglican tradition, which celebrates the human body as a sacred site and instrument of worship, a vessel for embodied prayer.

I think this may be a beautiful alternative to the American Protestant emphasis on the mind as the effective center of Christian spiritual life. “Confess and believe” is the marker for who’s in and who’s out in the evangelical community. What that often translates to in practice is a requirement to say the right things and think the right thoughts in order to be considered a Good Christian. I agree that speaking, confession, and belief are vital aspects of a Christian life, but I don’t think they are sufficient conditions of Christian faith.

Does Conrad fulfill the evangelical “requirement” to confess and believe? He can confess, but I’m not sure what kind of beliefs his lower-than-average IQ allows. We can’t know exactly how, or how much, he can comprehend. But he has been baptized. He has participated in church, in prayers, in communion. Perhaps liturgical Christians in the Catholic, Orthodox, and Anglican traditions might have more theological room for someone like Conrad, because they have defined belonging through embodied baptism into the Church, and simply partaking of the body of Jesus through the Eucharist.

But this train of thought becomes even more difficult. I wonder about those who might have physical impairments that make them unable to process or kneel or eat and drink during a service. I have been to several Chinese American churches that center their spiritual life around community and fellowship. Plenty of wisdom, love, and discernment—and gossip!—is passed during gatherings and over meals. But what about those like Chyle, who are happy to attend but can’t participate as fully in conversation? How does the Spirit work in communities of people who can’t speak, who can’t express their emotions “normally”? I could go on.

What is a practical definition of spirituality for myself and my brothers? Although God’s Spirit, and our spirits, can be engaged through all of these practices, spirituality must be distinct from any one practice. It has to be. There must be something more basic, more fundamental to life that describes the essence of the human spirit.

All forms of human expression—ornate architectural monuments, art, music, barbecues, athletics, festivals, gatherings, Holy feasts filled with food, dancing, prayer, theology, scriptural study, the Eucharist—are portals through which humanity may approach the liminal veil between heaven and earth. Each of these activities is valid and beautiful, and through each we can encounter the living Spirit of God in our terrestrial lives. But each activity is only one portal of many and cannot be treated as an exclusive pathway to God, at the cost of excluding other people—and certainly should not be misconstrued as the sole source of God’s presence and Spirit. The Spirit and our spirits must exist through these activities, and beyond any one of them.

The one thing we humans have in common, regardless of ability, is that we were made in God’s image. That is, we each have the Spirit that was breathed into our first father’s nostrils and lungs by God himself, the Spirit that was passed down through generations, the same Spirit-breath we each inhaled as we—bloody, coughing, and crying—emerged into the world. So perhaps it is not our thinking minds or feeling hearts or speaking voices or eating mouths that bring us to God, make us like God, but rather the breath that breathes the Spirit that God imparted to humanity at the very beginning. Maybe that is what the Psalmist meant when (s)he wrote “Let everything that has breath praise the Lord” (150:6a).

If everything that breathes, every human spirit, is capable of praising the Lord, my brothers and I are in a really good place.